From Atacama to Appalachia: The Woman Against All Odds

- Javiera Cotapos

- Dec 6, 2025

- 9 min read

The Nomad Child

In the heatstroke-inducing deserts of Northern Chile, nothing is safe from the sun. The ground cooks whatever dares to grow. The only thing to accompany the seemingly never-ending stretch of land is more land—miles and miles of it. The horizon becomes a doubtful, blurry idea in the mind’s eye.

But humans are a resilient creature group.

In a land full of extremes, the people of Northern Chile are adaptive, resourceful, logical and thick-skinned. These are only a few descriptors one would use for Cosset Campbell, 52, one of Northern Chile’s few natives who have found themselves across the oceans and now reside in Appalachia.

Cosset Campbell’s childhood goes by a different name. In her youth and until she married in 2015, she was Cosset Macarena Avalos Soriagalvarro. Her journey begins in the Atacama Desert, the driest desert in the world, where her family of three lived in a mud house without doors, windows or a roof. A makeshift roof made from metal scraps covered their heads from the unmerciful sun, and wooden planks on windows and thresholds offered them fragile protection from chilly nights.

“Cold is something deeply tied to poverty,” Campbell said. “And I remember that my siblings and I felt a lot of cold for many years.”

Her father was absent, always taking different jobs though they were few and in between, leaving her mother and two younger siblings on their own. Constantly moving due to their unstable financial situation, Cosset had gotten used to a nomadic lifestyle by the age of eight. The only familiar place in her child’s mind was her maternal grandparents’ house, which they would visit almost every weekend. It was not until her father moved her, her siblings and mother to Ovalle, a city in the Coquimbo Region of Chile, that she saw her first fruit tree: a peach tree. A new world flourished right before her eyes.

Ovalle is where she felt the coldest. Her family went to extreme lengths to provide food for survival; her mother even caught wild ducks to eat. Trees grew tall over the walls separating neighboring houses and the fruits that would hang conveniently in the streets were a plentiful source of snacks. When hunger is so dire, anything edible is taken as a treasure. Campbell remembers eating fruits off the ground that had fallen, devouring them so fast she didn’t register the taste.

“When you are a child, you don’t realize you are poor. You think everyone is just like you,” Cosset said. “You don’t understand social differences because you haven’t seen them—poverty is surrounded by more poverty, so there is nothing to compare it to.”

Life in Ovalle sizzled out quickly. When her father no longer returned home, it took Campbell’s mom’s smile with it. After many breakfasts for dinners, ant-riddled pots of sugar and a disappearing amount of food on the table, Campbell and her family traveled back to her beloved grandparents’ house in Calama.

Her life from then on was filled with military tanks, helicopters buzzing overhead and men in uniform acting as everyday citizens, though they were quick to snap into action when someone stepped out of line. This military coup was the result of Chile’s socialist president, who turned the country’s economy inside out, and one she would get to know closely in her future.

The Rocky Road

An economic shutdown occurred after Chile elected its first Socialist president, Salvador Allende. One of his main courses of action was expropriating businesses from external owners. At the time, U.S. franchises owned the most prominent companies with which they did business closely. When the U.S. caught wind of Chile’s new socialist ways, it was quick to impose an economic embargo, causing Chile’s economy to plummet.

During Allendes’ presidency, Chile suffered shortages across all categories, most notably in gas and food. Campbell’s mother, Nancy Sorrialvarro, had to stand in line at local markets for hours on end to buy food that was already rationed. Due to the length of the lines, she and Campbell’s grandmother, Eleanira, had to take turns to come out with something—sometimes, they’d come out with nothing as supplies ran out.

Allende’s presidency lasted three years. It ended tragically when the military rebelled and illegally took control of the country, bombing La Casa De La Moneda, the government house where the president resided. This was ordered by the Military Officer and soon-to-be Dictator Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, who would serve as president for the next 17 years. During this time, all liberal arts education was shut down. The media became one-sided and heavily biased in favor of the government. Assassinations were not rare; citizens who attempted to defy this faced lethal consequences from high officials. It wasn’t long before Chile’s democracy crumbled along with its freedom of speech.

“Being born during this time, the dictatorship did not mean much to me for my first 17 years of life,” Campbell said. “I saw them [the military] as much as I saw my neighbors or teachers.”

Campbell spent her elementary, middle and high school years under the dictatorship. The harsh political climate resulted in prison camps, which were made for opponents who secretly sought to end Pinochet’s reign but got caught. In the camps, these prisoners were tortured through cruel methods, disappeared or killed. Knowing the dangerous consequences, Campbell’s family did not discuss political matters. Instead, she focused solely on studying and getting good grades.

Her way out of poverty was education. When Cosset and her siblings found themselves at risk of taking other options to survive, such as prostitution, drugs, trafficking or alcoholism, all of which were prevalent in her community, her grandparents offered to take them to school. Seeing the potential, Cosset worked hard to earn good grades throughout her academic career, winning awards such as the best student in the region. Her grandfather helped her get into Universidad Del Mar in Antofagasta. What he saw in her most was her drive and responsibility as the eldest child.

“Education opened up a lot of doors for me and changed not only my life, but also my family’s,” Campbell said.

After the dictatorship that seemed to last a lifetime ended, Chile regained democracy when Patricio Aylwin was elected president, seeking to restore power to the people. The press was relieved of its strict shackles and the media was more than ready to get back into action. In her first year of college, Campbell was hired by the Chilean government to work part-time at a city hall in Antofagasta. On weekends, she trained in war coverage, learned to shoot firearms, use a compass, camouflage, understand class hierarchy and military strategy and engage in strenuous physical exercise. Despite her hard work, she never got to participate because Chile had no wars; the last war having taken place in 1879. Her passion for writing, reporting and communications was blossoming. She was the first woman journalist in the area after the dictatorship.

Campbell at 18 years old getting war coverage training in March of 1989 at Regimiento 7 de Linea Esmeralda, Antofagasta, Chile.

Personal Persecution

Life went on while Campbell was gaining an audience for multiple outlets. It was through “El Mercurio” that she found her key to the big leagues of reporting. She soon broke into an editor position and was quickly climbing the ladder. In her third year of working, she was able to start fully supporting her family. Some other outlets she contributed to were “La Estrella” and “Oasis,” as editor and director. In her journalism career, Campbell covered natural disasters — which Chile had an abundance of, being an earthquake hotspot — police work, concerts, events and mining news. She flew on army helicopters for some of her coverage and has been inside mines around the world, from Canada to Mexico.

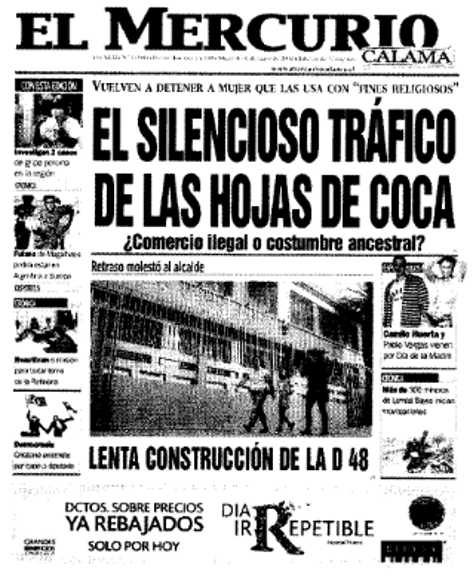

Covers of “El Mercurio” newspaper for Chile, South America, where Campbell was a reporter and executive editor from 1990 to 1996. During this time, women could not serve as the director of this newspaper per the company's policy, which made executive editor the highest rank she could reach.

“Journalism was the window to the world for me because I began seeing other realities,” Campbell said. “When a poor family offers you a dirty glass of water, you drink it, for the connection.”

One time, she had to cover a rat infestation at a house. When she entered the house, she first saw medium-sized rocks scattered across the floor. She thought it was odd, but not the wildest thing she had witnessed as a journalist. Halfway through her interview, the rocks began moving—the rats had dug holes through the floor from underneath the house and had moved in, rent-free.

Another time, when she was an executive editor, she sent one of her photographers to cover a major bus crash at a mining site. When her photographer came back, Campbell saw them leaning against a wall, crying. She asked what was wrong. The photographer replied that what they thought was mud on their shoes was the victim’s insides, which had piled up gruesomely at the scene of the accident. They had dragged it into the studio.

One of the key tactics she picked up on the job was learning to find hidden people — the often overlooked yet active folks in the area such as waitresses, bartenders, security guards, janitors and maintenance workers. These people granted her access, information and insights as walking cameras since they kept a low profile but secretly had first row seats to everything.

Everything changed when she was offered a position at a mining company in Codelco Norte, Chuquicamata, in the Department of Communication, where she would work for 12 years. Codelco was the biggest mining company in all of Chile and one of the most important copper reserves in the world. Though the pay was good, the work was tough. As a woman in a male-dominated industry, she found herself working harder to gain her co-workers' respect than to do her actual job.

Only 10 days into her new position, Campbell’s boss suddenly quit without notice. This made her the new boss of the department at only 26 years old, a sick joke only she seemed to be the butt of. Where challenges appeared, her drive to succeed only heightened, but not without her boundaries and personal conduct being tested.

“The company was politically structured; it was very organized in who they wanted to work with and who they wanted to be tied to,” Campbell said. “You could not grow in the company just by hard work; you had to belong to a certain party, and I did not want to be part of that game.”

The decision not to identify herself with a political party had serious consequences. Write-ups were rare in the industry, but she received four, all unrelated to her job performance. These notices warned her of her personal affiliations; they stated that she could not talk to certain people or even be seen with them for the company’s sake. She soon realized her company did not have her back as she had theirs. Another company that was fighting to secure a contract with Codelco sent Campbell a death threat after she declined their proposal. This letter would first reach her boss, who would hand it to her with no offer of protection or lawyers—it was simply her problem and hers alone.

“When they told me I could not even see people I chose to, it made it clear that it was a political persecution,” Campbell said.

This was only the beginning of her realization that Chile might not be her forever home.

In Appalachia

In 2011, Campbell arrived at McGhee Tyson Airport, Knoxville, Tennessee, with her two children, 8-and 10-year-olds. With no knowledge of English, they dived headfirst into American culture and submerged themselves in the language up to their noses. Campbell had traveled to study on a student Visa, but it was tough as an immigrant mother of two. Sacrifices were made and risks were taken. During this time, her schedule with classes did not align with her kids’ and they were often left to wait for her to pick them up at a nearby gas station where the school bus dropped them off. Her phone became a lifeline. In a country so unbeknownst to them, in people and in language, they only had each other.

“It was not only language I had to learn, but it was also money, traffic rules, personal space—everyone in Chile hugs and kisses and smothers each other with affection,” Campbell said.

It took one too many awkward and embarrassing moments for her to catch on and learn.

Despite the circumstances, Campbell succeeded in her education at Maryville College, remaining the good student she had always been. While studying, she continued in her journalism journey and became an editor for a Hispanic newsletter. The success of the newsletter landed her a TV interview, yet another impressive mark on her lengthy resume. All the while, she was still being asked for interviews back at home in Chile. Once a reporter, Campbell became the subject of many articles written over her tumultuous professional life. After countless nights of studying locked away in her room, she earned a scholarship that allowed her to become a Spanish teacher.

Second from the left, Campbell on set with WVLT Volunteer TV on Dec. 18, 2013, for an interview after they heard of her work at Maryville College, in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Her next big goal after becoming licensed was fighting for her citizenship. Though it took five years and a lot of money, in 2023, she became a United States citizen. Since then, she has worked at Jefferson County High School and currently works in Sevierville County High School as a Spanish educator, where her skills and personality are adored by many. As a side hustle, she also gives back to the community by driving school buses.

In her life, Campbell has walked many different paths. She became a voice of the people and covered issues in society such as poverty, domestic violence and hard news. Her reporter background followed her to the United States, where she covered the lives of other immigrants at her college. Now, she continues to support her community in Sevierville, surrounded by mountains and greenery, something her childhood self would have never imagined.

“It’s not about the things one achieves; it’s about going for it,” Campbell said. “Take every opportunity you can; the worst thing that can happen is you stay in the same place.”

Comments